Sheikh Bilal and the sheikh of Deir al Hatab

On our way to Deir al-Hatab we stopped to see what had changed at Maqam Sheikh Bilal which is crumbling away on the Jabal Kabir ridge, which Israel designated as a nature preserve, accessible only through the Alon Moreh settlement. Since there is much private Palestinian land on the ridge belonging to villagers from Deir al-Hatab, Salem and Azmut, the lands are easy prey for settlers from Alon Moreh and its outposts.

We found a new banner hung on the fence surrounding the maqam announcing the initiation of the “Alon Moreh Heritage Center,” located within the settlement, inviting visitors. Extensive development is visible everywhere on the ridge: thistles have been mowed down, new paths laid, particularly near the memorial for the late Brigadier General Yosef Lunz (Luntzi), an orientalist, a scout, a friend, commander, fighter, who loved his land.” The memorial to Lunz is fixed on a boulder shaded by an impressive oak, facing Nahal Tirza’s ancient landscape lying below.

Two of the four topics offered are devoted to nature (presented by Ayala and Iris) and two to a general history of settlements in Samaria, Alon Moreh in particular.

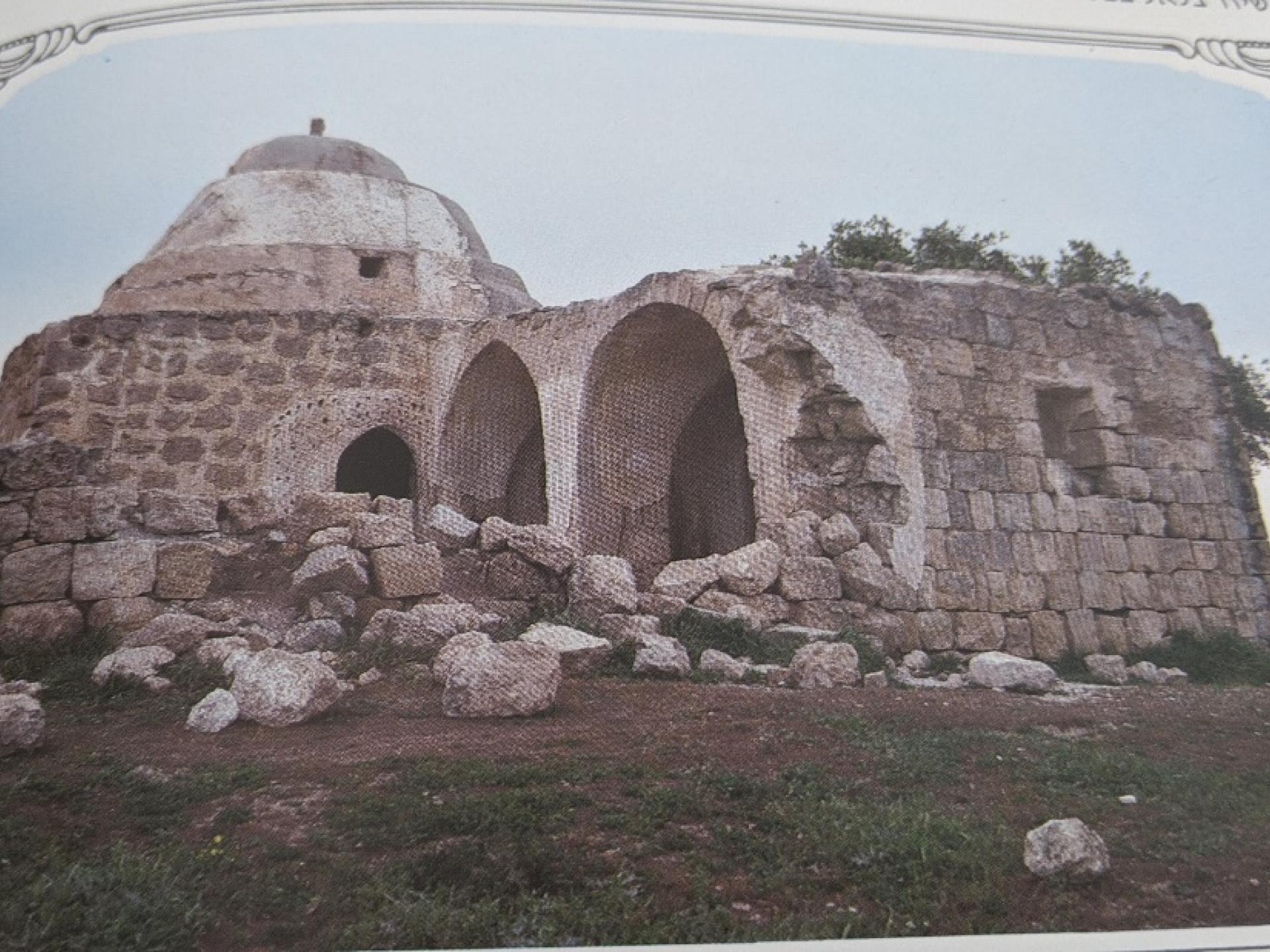

There’s no reference to the heritage of the villages on whose lands Alon Moreh was established. Maqam Sheikh Bilal, with its unique stepped dome, was built some 400 years ago (according to the archaeologist Gideon Solimani’s), to commemorate Islam’s first muezzin. Its present deterioration shows the Israeli occupation’s attitude toward Palestinian religious and historical assets and demonstrates the continuing violation of the rights of the occupied population to maintain its religious ceremonies and preserve its heritage sites. The Palestinians would be happy to restore it with their own hands, we were told by Ismail Abed Ismail, Deir al-Hatab’s sheikh and imam. “If they’d only let us access it,” he said later in the day, at home in Deir al-Hatab.

Ismail Abed Ismail was born in 1960 on agricultural land next to the maqam. “It was usual to work and live on the agricultural land outside the village during most of the year.” His family has four large plots of agricultural land trapped within the settlement’s fence.

The occupation authorities permit harvesting olives only for a limited number of days and forbid the use of vehicles. The entire family, numbering 30 individuals, goes together, from oldest to youngest. The yield diminishes from year to year because the settlers have taken over the family’s lands and repeatedly damage the trees. Ismail has a phenomenal memory; he quotes from his memory the declining olive harvest and oil production numbers from year to year. They’re not allowed to access the water cisterns on site. The settlers turned one of the cisterns into a wading pool. He marked on a map I’d brought the exact location of each cistern. He proposed that during the olive harvest we meet him on their lands. He'll arrive on foot with his family, and we by car through the settlement’s entrance gate (since he knows we’d be prevented from joining the family to enter their land otherwise). Ismail’s pain is evident in every word he speaks. He’s exiled in his own land.

More information about the lands of Deir al-Hatab, Salem and Azmut can be found in the 2016 B’Tselem report, “Expulsion-Construction-Exploitation,” the Israeli method for taking control of rural Palestine. An interview with Ismail Abed Ismail appears on p. 18. An interview with him also appears on p. 17 of the maqam survey (available on Machsom Watch’s website).